University of Transnational Business Law

Main menu

- HOME PAGE

-

INFORMATION

-

ENCYCLOPEDIA

- Argumentation in the law

- The Argument from Coherence

- Teleological Argumentation

- Berlin, Isaiah, British philosopher, historian of ideas and political theorist

- Capital Punishment

- Common Law

- Context of Discovery, Context of Decision and Context of Justification in the Law

- Constitutionalism

- Deontic Logic

- Value-Based Disobedience

- Duty - Moral and Political

- Equality as Legal Argument

- Reflective Equilibrium

- Fuller, Lon Luvois, The most renowned American legal theorist in the middle decades of the 20th century,

- Game theory in jurisprudence

- Legal gaps

- Grotius, Hugo, Philosophy

- Hägerström, Axel,

- Harm

- Hermeneutical legal theory

- Ideals in law

- Indeterminacy in the law: Types and problems

- Institutionalist theories of law

- The Binding Force of International Law

- The EU and International Law

- Interpretation of law

- Constitutional Interpretation (in Continental Europe)

- Islamic legal theory

- Philosophy of Jewish Law

- Jörgensen’s Dilemma

- Judicial Review of Statutes

- Normative and Analytic Jurisprudence

- Jus Cogens

- The Concept of Law

- Law and Bioethics

- Law and Defeasibility

- Law and Economics - Main Entry

- Law and Economics - Contracts

- Law and Economics - Ethics, Economics, and Adjudicatio

- Law and Literature

- Law and Policy

- Law and Politics

- Law as Integrity

- Legal Certainty

- fundamental legal concepts (Yale)

- Joseph Raz's Legal Philosophy

- Kant's Legal Philosophy

- Legal Positivism

- Legal Positivism: Critical Assessment and Epistemological Reflexions

- The Concept of Legal Competence

- Descriptive Legal Theory

- Legal Theory: Types and Purposes

- Liberty

- Logic and Law

- Same Sex Marriage

- Natural Law

- Objectivity of Law

- Objectivity of Legal Science

- Perelman, Chaim

- Political representation in the European Union

- Positive Law and Natural Law

- Possible Right Holders

- Practical Argumentation in the Justification of Judicial Decisions

- Precedent

- Rules and Principles

- Proportionality review in European law

- Ratio Decidendi

- A. John Rawls: Introduction to Rawls’s Project

- B. John Rawls: His Two Principles and Their Application

- C. John Rawls: The Original Position Argument

- D. John Rawls: Procedural Justice and Legitimacy

- E. John Rawls: Justification and Objectivity

- F. John Rawls: Political Liberalism

- G. John Rawls: The Law of Peoples

- H. John Rawls: Some Main Lines of Criticism

- I. John Rawls: Bibliography

- Rhetoric

- Rights

- Conceptions of Rights in Recent Anglo-american Philosophy

- Human Rights and Globalization

- Legal and Moral Rights

- Rights Conflict

- Ross, Alf

- Rule of Law - Philosophical Perspectives

- Scandinavian Realism

- Structuralist Semiotics of Law

- Standing in the Law of the Commonwealth and in International Law

- Tort Law as Corrective Justice

- Valid Law Reconsidered

- Level 2

- INFORMATION

- UN LIve TV

- DARK INTENTIONS

- THE HUMANIST CONSPIRACY

- MARXISM ON CAMPUS

- CULTURAL MARXISM: The Corruption of America

- FIAT EMPIRE: Why the Federal Reserve Violates the U.S. Constitution

- CORPORATE FASCISM: The Destruction of America's Middle Class

- Former KGB Agent Explains how Elites Brainwash The Pulic from reality

- America: Freedom to Fascism

- WHO RUNS THE WORLD

- NEW WORLD ORDER

- MOLON LABE - Full Movie

- SPOiLER: How a Third Political Party Could Win

- MOTIVATION

-

RESOURCES

- GLOBAL TERMS

- AGENDA 21

- BAR EXAM QUESTIONS

- CHINA IMPORT EXPORT

- CRIMINAL TERMS ENGLISH TO CHINESE

- CHINESE GLOSSARY OF LEGAL TERMS

- ZHONGWEN

- INTERNATIONAL CONTRACTS

- COUNTRY REPORTS

- CULTURES

- CUSTOMARY RULES

- ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL

- EXPORTING

- GENEVA CONVENTIONS

- HUMAN RIGHTS

- INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE

- INTERNATIONAL LABOR ORGANIZATIONS

- INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

- INTERNATIONAL TRADE

- TELECOMUNICATIONS

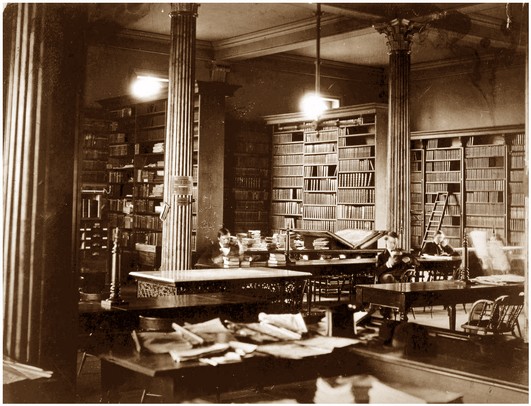

- LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

- NATO

- NEGOTIATE

- PATENTS

- PHOTOGRAPHY ETHICS

- TRANSLATOR

- TYPES OF RELIGION

- U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE

- UNESCO

- UNITED NATIONS

- USGS

- VALUES

- WORLD BANK

- WORLD FACTS

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

- INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

- WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION

-

ENCYCLOPEDIA

- REGISTRATION

- ENROLL

- ABOUT US

-

CIRRICULUM

- CIRRICULUM

-

Subjects

- Press "ctrl" and scroll down

- Semester 1

-

Success in College

- Table of Contents

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Chapter 1: You and Your College Experience

- 1.1 Who Are You, Really?

- 1.2 Different Worlds of Different Students

- 1.3 How You Learn

- 1.4 What Is College, Really?

- 1.5 Let’s Talk about Success

- 1.6 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2 Staying Motivated, Organized, and On Track

- 2.1 Setting and Reaching Goals

- 2.2 Organizing Your Space

- 2.3 Organizing Your Time

- 2.4 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3 Thinking about Thought

- 3.1 Types of Thinking

- 3.2 It’s Critical

- 3.3 Searching for “Aha!”

- 3.4 Problem Solving and Decision Making

- 3.5 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4 Listening, Taking Notes, and Remembering

- 4.1 Setting Yourself Up for Success

- 4.2 Are You Ready for Class?

- 4.3 Are You Really Listening?

- 4.4 Got Notes?

- 4.5 Remembering Course Materials

- 4.6 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5 Reading to Learn

- 5.1 Are You Ready for the Big Leagues?

- 5.2 How Do You Read to Learn?

- 5.3 Dealing with Special Texts

- 5.4 Building Your Vocabulary

- 5.5 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 6 Preparing for and Taking Tests

- 6.1 Test Anxiety and How to Control It

- 6.2 Studying to Learn (Not Just for Tests)

- 6.3 Taking Tests

- 6.4 The Secrets of the Q and A’s

- 6.5 The Honest Truth

- 6.6 Using Test Results

- 6.7 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7 Interacting with Instructors and Classes

- 7.1 Why Attend Classes at All?

- 7.2 Participating in Class

- 7.3 Communicating with Instructors

- 7.4 Public Speaking and Class Presentations

- 7.5 Chapter Activities

- Page 862

- Chapter 8 Writing for Classes

- 8.1 What’s Different about College Writing?

- 8.2 How Can I Become a Better Writer?

- 8.3 Other Kinds of Writing in College Classes

- 8.4 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9 The Social World of College

- 9.1 Getting Along with Others

- 9.2 Living with Diversity

- 9.3 Campus Groups

- 9.4 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10 Taking Control of Your Health

- 10.1 Nutrition and Weight Control

- 10.2 Activity and Exercise

- 10.3 Sleep

- 10.4 Substance Use and Abuse

- 10.5 Stress

- 10.6 Emotional Health and Happiness

- 10.7 Sexual Health

- 10.8 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11 Taking Control of Your Finances

- 11.1 Financial Goals and Realities

- 11.2 Making Money

- 11.3 Spending Less

- 11.4 Credit Cards

- 11.5 Financing College and Looking Ahead

- 11.6 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12 Taking Control of Your Future

- 12.1 The Dream of a Lifetime

- 12.2 Career Exploration

- 12.3 Choosing Your Major

- 12.4 Getting the Right Stuff

- 12.5 Career Development Starts Now

- 12.6 The Power of Networking

- 12.7 Résumés and Cover Letters

- 12.8 Interviewing for Success

- 12.9 Chapter Activities

- Chapter 12

- Test

-

English for Business Success

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Dedications

- Preface

- 1.1 Sentence Writing

- 1.2 Subject-Verb Agreement

- 1.3 Verb Tense

- 1.4 Capitalization

- 1.5 Pronouns

- 1.6 Adjectives and Adverbs

- 1.7 Misplaced and Dangling Modifiers

- 1.8 Writing Basics: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 1 Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?

- 2.1 Commas

- 2.2 Semicolons

- 2.3 Colons

- 2.4 Quotes

- 2.5 Apostrophes

- 2.6 Parentheses

- 2.7 Dashes

- 2.8 Hyphens

- 2.9 Punctuation: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 2 Punctuation

- 3.1 Commonly Confused Words

- 3.2 Spelling

- 3.3 Word Choice

- 3.4 Prefixes and Suffixes

- 3.5 Synonyms and Antonyms

- 3.6 Using Context Clues

- 3.7 Working with Words: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 3 Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?

- 4.1 Word Order

- 4.2 Negative Statements

- 4.3 Count and Noncount Nouns and Articles

- 4.4 Pronouns

- 4.5 Verb Tenses

- 4.6 Modal Auxiliaries

- 4.7 Prepositions

- 4.8 Slang and Idioms

- 4.9 Help for English Language Learners: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 4 Help for English Language Learners

- 5.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

- 5.2 Effective Means for Writing a Paragraph

- 5.3 Writing Paragraphs: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 5 Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content

- 6.1 Sentence Variety

- 6.2 Coordination and Subordination

- 6.3 Parallelism

- 6.4 Refining Your Writing: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 6 Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?

- 7.1 Apply Prewriting Models

- 7.2 Outlining

- 7.3 Drafting

- 7.4 Revising and Editing

- 7.5 The Writing Process: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 7 The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?

- 8.1 Developing a Strong, Clear Thesis Statement

- 8.2 Writing Body Paragraphs

- 8.3 Organizing Your Writing

- 8.4 Writing Introductory and Concluding Paragraphs

- 8.5 Writing Essays: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 8 Writing Essays: From Start to Finish

- Chapter 9 Effective Business Writing

- 9.1 Oral versus Written Communication

- 9.2 How Is Writing Learned?

- 9.3 Good Writing

- 9.4 Style in Written Communication

- 9.5 Principles of Written Communication

- 9.6 Overcoming Barriers to Effective Written Communication

- 9.7 Additional Resources

- Chapter 9 Effective Business Writing

- Chapter 10 Writing Preparation

- 10.1 Think, Then Write: Writing Preparation

- 10.2 A Planning Checklist for Business Messages

- 10.3 Research and Investigation: Getting Started

- 10.4 Ethics, Plagiarism, and Reliable Sources

- 10.5 Completing Your Research and Investigation

- 10.6 Reading and Analyzing

- 10.7 Additional Resources

- Chapter 10 Writing Preparation

- Chapter 11 Writing

- 11.1 Organization

- 11.2 Writing Style

- 11.3 Making an Argument

- 11.4 Paraphrase and Summary versus Plagiarism

- 11.5 Additional Resources

- Chapter 11 Writing

- Chapter 12 Revising and Presenting Your Writing

- 12.1 General Revision Points to Consider

- 12.2 Specific Revision Points to Consider

- 12.3 Style Revisions

- 12.4 Evaluating the Work of Others

- 12.5 Proofreading and Design Evaluation

- 12.6 Additional Resources

- Chapter 12 Revising and Presenting Your Writing

- Chapter 13 Business Writing in Action

- 13.1 Text, E-mail, and Netiquette

- 13.2 Memorandums and Letters

- 13.3 Business Proposal

- 13.4 Report

- 13.5 Résumé

- 13.6 Sales Message

- 13.7 Additional Resources

- Chapter 13 Business Writing in Action

- 14.1 Formatting a Research Paper

- 14.2 Citing and Referencing Techniques

- 14.3 Creating a References Section

- 14.4 Using Modern Language Association (MLA) Style

- 14.5 APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 14 APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting

-

Writers' Handbook

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Preface to Teachers

- Preface to Students

- 1.1 Examining the Status Quo

- 1.2 Posing Productive Questions

- 1.3 Slowing Down Your Thinking

- 1.4 Withholding Judgment

- Chapter 1 Writing to Think and Writing to Learn

- 2.1 Browsing the Gallery of Web-Based Texts

- 2.2 Understanding How Critical Thinking Works

- 2.3 Reading a Text Carefully and Closely

- Chapter 2 Becoming a Critical Reader

- 3.1 Exploring Academic Disciplines

- 3.2 Seeing and Making Connections across Disciplines

- 3.3 Articulating Multiple Sides of an Issue

- Chapter 3 Thinking through the Disciplines

- 4.1 Raising the Stakes by Going Public

- 4.2 Recognizing the Rhetorical Situation

- 4.3 Rhetoric and Argumentation

- 4.4 Developing a Rhetorical Habit of Mind

- Chapter 4 Joining the Conversation

- 5.1 Choosing a Topic

- 5.2 Freewriting and Mapping

- 5.3 Developing Your Purposes for Writing

- 5.4 Outlining

- Chapter 5 Planning

- 6.1 Forming a Thesis

- 6.2 Testing a Thesis

- 6.3 Supporting a Thesis

- 6.4 Learning from Your Writing

- 6.5 Learning from Your Reading

- 6.6 Generating Further Questions

- 6.7 Using a Variety of Sentence Formats

- 6.8 Creating Paragraphs

- Chapter 6 Drafting

- 7.1 Organizing Research Plans

- 7.2 Finding Print, Online, and Field Sources

- 7.3 Choosing Search Terms

- 7.4 Conducting Research

- 7.5 Evaluating Sources

- 7.6 Taking Notes

- 7.7 Making Ethical and Effective Choices

- 7.8 Creating an Annotated Bibliography

- 7.9 Managing Information

- Chapter 7 Researching

- 8.1 Reviewing for Purpose

- 8.2 Editing and Proofreading

- 8.3 Making a Final Overview

- Chapter 8 Revising

- 9.1 General Text Formatting Considerations

- 9.2 Creating and Finding Visuals

- 9.3 Incorporating Images, Charts, and Graphs

- Chapter 9 Designing

- 10.1 Choosing a Document Design

- 10.2 Developing Digital Presentations

- 10.3 Presenting Orally

- Chapter 10 Publishing

- 11.1 Meeting College Writing Expectations

- 11.2 Using Strategies for Writing College Essays

- 11.3 Collaborating on Academic Writing Projects

- Chapter 11 Academic Writing

- 12.1 Writing Business Letters

- 12.2 Writing to Apply for Jobs

- 12.3 Composing Memos

- 12.4 E-mail and Online Networking

- Chapter 12 Professional Writing

- 13.1 Composing in Web-Based Environments

- 13.2 Creating Websites

- 13.3 Collaborating Online

- 13.4 Creating an E-portfolio

- 13.5 Using Web Links Effectively

- Chapter 13 Writing on and for the Web

- 14.1 Writing Newsletters

- 14.2 Creating Flyers and Brochures

- 14.3 Developing Ads

- 14.4 Writing Personal Letters

- Chapter 14 Public and Personal Writing

- 15.1 Incorporating Core Sentence Components (Avoiding Fragments)

- 15.2 Choosing Appropriate Verb Tenses

- 15.3 Making Sure Subjects and Verbs Agree

- 15.4 Avoiding Misplaced Modifiers, Dangling Modifiers, and Split Infinitives

- 15.5 Preventing Mixed Constructions

- 15.6 Connecting Pronouns and Antecedents Clearly

- Chapter 15 Sentence Building

- 16.1 Using Varied Sentence Lengths and Styles

- 16.2 Writing in Active Voice and Uses of Passive Voice

- 16.3 Using Subordination and Coordination

- 16.4 Using Parallelism

- 16.5 Avoiding Sexist and Offensive Language

- 16.6 Managing Mood

- Chapter 16 Sentence Style

- 17.1 Controlling Wordiness and Writing Concisely

- 17.2 Using Appropriate Language

- 17.3 Choosing Precise Wording

- 17.4 Using the Dictionary and Thesaurus Effectively

- Chapter 17 Word Choice

- 18.1 Using Commas Properly

- 18.2 Avoiding Unnecessary Commas

- 18.3 Eliminating Comma Splices and Fused Sentences

- 18.4 Writing with Semicolons and Colons

- 18.5 Using Apostrophes

- 18.6 Using Quotation Marks

- 18.7 Incorporating Dashes and Parentheses

- 18.8 Choosing Correct End Punctuation

- 18.9 Knowing When to Use Hyphens

- Chapter 18 Punctuation

- 19.1 Mastering Commonly Misspelled Words

- 19.2 Using Capital Letters

- 19.3 Abbreviating Words and Using Acronyms

- 19.4 Inserting Numbers into Text

- 19.5 Marking Words with Italics

- Chapter 19 Mechanics

- 20.1 Making Sure Subject and Verbs Agree

- 20.2 Avoiding General Verb Problems

- 20.3 Choosing the Correct Pronoun and Noun Cases

- 20.4 Making Pronouns and Antecedents Agree

- 20.5 Using Relative Pronouns and Clauses

- 20.6 Using Adverbs and Adjectives

- Chapter 20 Grammar

- Chapter 21 Appendix A: Writing for Nonnative English Speakers

- 21.1 Parts of Speech

- 21.2 English Word Order

- 21.3 Count and Noncount Nouns

- 21.4 Articles

- 21.5 Singulars and Plurals

- 21.6 Verb Tenses

- 21.7 Correct Verbs

- 21.8 Modal Auxiliary Verbs

- 21.9 Gerunds and Infinitives

- 21.10 Forming Participles

- 21.11 Adverbs and Adjectives

- 21.12 Irregular Adjectives

- 21.13 Indefinite Adjectives

- 21.14 Predicate Adjectives

- 21.15 Clauses and Phrases

- 21.16 Relative Pronouns and Clauses

- 21.17 Prepositions and Prepositional Phrases

- 21.18 Omitted Words

- 21.19 Not and Other Negative Words

- 21.20 Idioms

- 21.21 Spelling Tips

- 21.22 American Writing Styles, Argument, and Structure

- Chapter 21 Appendix A: Writing for Nonnative English Speakers

- Chapter 22 Appendix B: A Guide to Research and Documentation

- 22.1 Choosing a Documentation Format

- 22.2 Integrating Sources

- 22.3 Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

- 22.4 Formatting In-Text References

- 22.5 Developing a List of Sources

- 22.6 Using Other Formats

- Chapter 22 Appendix B: A Guide to Research and Documentation

-

Beginning Human Relations

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Preface

- Chapter 1 What Is Human Relations?

- 1.1 Why Study Human Relations?

- 1.2 Human Relations: Personality and Attitude Effects

- 1.3 Human Relations: Perception’s Effect

- 1.4 Human Relations: Self-Esteem and Self-Confidence Effects

- 1.5 Summary and Exercise

- Chapter 1 What Is Human Relations?

- Chapter 2 Achieve Personal Success

- 2.1 Emotional Intelligence

- 2.2 Goal Setting

- 2.3 Continuous Learning

- 2.4 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 2 Achieve Personal Success

- Chapter 3 Manage Your Stress

- 3.1 Types of Stress

- 3.2 Symptoms of Stress

- 3.3 Sources of Stress

- 3.4 Reducing Stress

- 3.5 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 3 Manage Your Stress

- 4.1 Verbal and Written Communication Strategies

- 4.2 Principles of Nonverbal Communication

- 4.3 Nonverbal Communication Strategies

- 4.4 Public Speaking Strategies

- 4.5 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 4 Communicate Effectively

- Chapter 5 Be Ethical at Work

- 5.1 An Ethics Framework

- 5.2 Making Ethical Decisions

- 5.3 Social Responsibility

- 5.4 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 5 Be Ethical at Work

- hapter 6 Understand Your Motivations

- 6.1 Human Motivation at Work

- 6.2 Strategies Used to Increase Motivation

- 6.3 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 6 Understand Your Motivations

- 7.1 What Is a Group?

- 7.2 Group Life Cycles and Member Roles

- 7.3 Effective Group Meetings

- 7.4 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 7 Work Effectively in Groups

- 8.1 Understanding Decision Making

- 8.2 Faulty Decision Making

- 8.3 Decision Making in Groups

- 8.4 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 8 Make Good Decisions

- 9.1 Understanding Conflict

- 9.2 Causes and Outcomes of Conflict

- 9.3 Conflict Management

- 9.4 Negotiations

- 9.5 Ethical and Cross-Cultural Negotiations

- 9.6 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 9 Handle Conflict and Negotiation

- Chapter 10 Manage Diversity at Work

- 10.1 Diversity and Multiculturalism

- 10.2 Multiculturalism and the Law

- 10.3 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 10 Manage Diversity at Work

- Chapter 11 Work with Labor Unions

- 11.1 The Nature of Unions

- 11.2 Collective Bargaining

- 11.3 Grievance Process

- 11.4 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 11 Work with Labor Unions

- Chapter 12 Be a Leader

- 12.1 Management Styles

- 12.2 Leadership versus Management

- 12.3 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 12 Be a Leader

- Chapter 13 Manage Your Career

- 13.1 Career Growth: Power Positioning and Power Sources

- 13.2 Career Growth: Behaviors and Change

- 13.3 Career Growth: Impression Management

- 13.4 Career Growth: Personality and Strategies

- 13.5 Chapter Summary and Case

- Chapter 13 Manage Your Career

-

Beginning Algebra

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- 1.1 Real Numbers and the Number Line

- 1.2 Adding and Subtracting Integers

- 1.3 Multiplying and Dividing Integers

- 1.4 Fractions

- 1.5 Review of Decimals and Percents

- 1.6 Exponents and Square Roots

- 1.7 Order of Operations

- 1.8 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 1 Real Numbers and Their Operations

- 2.1 Introduction to Algebra

- 2.2 Simplifying Algebraic Expressions

- 2.3 Solving Linear Equations: Part I

- 2.4 Solving Linear Equations: Part II

- 2.5 Applications of Linear Equations

- 2.6 Ratio and Proportion Applications

- 2.7 Introduction to Inequalities and Interval Notation

- 2.8 Linear Inequalities (One Variable)

- 2.9 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 2 Linear Equations and Inequalities

- 3.1 Rectangular Coordinate System

- 3.2 Graph by Plotting Points

- 3.3 Graph Using Intercepts

- 3.4 Graph Using the y-Intercept and Slope

- 3.5 Finding Linear Equations

- 3.6 Parallel and Perpendicular Lines

- 3.7 Introduction to Functions

- 3.8 Linear Inequalities (Two Variables)

- 3.9 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 3 Graphing Lines

- 4.1 Solving Linear Systems by Graphing

- 4.2 Solving Linear Systems by Substitution

- 4.3 Solving Linear Systems by Elimination

- 4.4 Applications of Linear Systems

- 4.5 Solving Systems of Linear Inequalities (Two Variables)

- 4.6 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 4 Solving Linear Systems

- 5.1 Rules of Exponents

- 5.2 Introduction to Polynomials

- 5.3 Adding and Subtracting Polynomials

- 5.4 Multiplying Polynomials

- 5.5 Dividing Polynomials

- 5.6 Negative Exponents

- 5.7 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 5 Polynomials and Their Operations

- 6.1 Introduction to Factoring

- 6.2 Factoring Trinomials of the Form x^2 + bx + c

- 6.3 Factoring Trinomials of the Form ax^2 + bx + c

- 6.4 Factoring Special Binomials

- 6.5 General Guidelines for Factoring Polynomials

- 6.6 Solving Equations by Factoring

- 6.7 Applications Involving Quadratic Equations

- 6.8 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 6 Factoring and Solving by Factoring

- 7.1 Simplifying Rational Expressions

- 7.2 Multiplying and Dividing Rational Expressions

- 7.3 Adding and Subtracting Rational Expressions

- 7.4 Complex Rational Expressions

- 7.5 Solving Rational Equations

- 7.6 Applications of Rational Equations

- 7.7 Variation

- 7.8 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 7 Rational Expressions and Equations

- 8.1 Radicals

- 8.2 Simplifying Radical Expressions

- 8.3 Adding and Subtracting Radical Expressions

- 8.4 Multiplying and Dividing Radical Expressions

- 8.5 Rational Exponents

- 8.6 Solving Radical Equations

- 8.7 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 8 Radical Expressions and Equations

- 9.1 Extracting Square Roots

- 9.2 Completing the Square

- 9.3 Quadratic Formula

- 9.4 Guidelines for Solving Quadratic Equations and Applications

- 9.5 Graphing Parabolas

- 9.6 Introduction to Complex Numbers and Complex Solutions

- 9.7 Review Exercises and Sample Exam

- Chapter 9 Solving Quadratic Equations and Graphing Parabolas

- Chapter 10 Appendix: Geometric Figures

- 10.1 Plane

- 10.2 Solid

- Page 859

- Semester 2

-

Using Microsoft Excel 1.1

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1.1 An Overview of Microsoft® Excel®

- 1.2 Entering, Editing, and Managing Data

- 1.3 Formatting and Data Analysis

- 1.4 Printing

- 1.5 Chapter Assignments and Tests

- Chapter 1 Fundamental Skills

- 2.1 Formulas

- 2.2 Statistical Functions

- 2.3 Functions for Personal Finance

- 2.4 Chapter Assignments and Tests

- Chapter 2 Mathematical Computations

- 3.1 Logical Functions

- 3.2 Statistical IF Functions

- 3.3 Lookup Functions

- 3.4 Chapter Assignments and Tests

- Chapter 3 Logical and Lookup Functions

- 4.1 Choosing a Chart Type

- 4.2 Formatting Charts

- 4.3 The Scatter Chart

- 4.4 Using Charts with Microsoft® Word® and Microsoft® PowerPoint®

- 4.5 Chapter Assignments and Tests

- Chapter 4 Presenting Data with Charts

-

Using Microsoft Excel 1.0

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1.1 An Overview of Microsoft® Excel®

- 1.2 Entering, Editing, and Managing Data

- 1.3 Formatting and Data Analysis

- 1.4 Printing

- 1.5 Chapter Assignments and Tests

- Chapter 1 Fundamental Skills

- 2.1 Formulas

- 2.2 Statistical Functions

- 2.3 Functions for Personal Finance

- 2.4 Chapter Assignments and Tests

- Chapter 2 Mathematical Computations

- 3.1 Logical Functions

- 3.2 Statistical IF Functions

- 3.3 Lookup Functions

- 3.4 Chapter Assignments and Tests

- Chapter 3 Logical and Lookup Functions

- 4.1 Choosing a Chart Type

- 4.2 Formatting Charts

- 4.3 The Scatter Chart

- 4.4 Using Charts with Microsoft® Word® and Microsoft® PowerPoint®

- 4.5 Chapter Assignments and Tests

-

Successful Writing

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Dedications

- Preface

- 1.1 Reading and Writing in College

- 1.2 Developing Study Skills

- 1.3 Becoming a Successful College Writer

- 1.4 Introduction to Writing: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 1 Introduction to Writing

- 2.1 Sentence Writing

- 2.2 Subject-Verb Agreement

- 2.3 Verb Tense

- 2.4 Capitalization

- 2.5 Pronouns

- 2.6 Adjectives and Adverbs

- 2.7 Misplaced and Dangling Modifiers

- 2.8 Writing Basics: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 2 Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?

- 3.1 Commas

- 3.2 Semicolons

- 3.3 Colons

- 3.4 Quotes

- 3.5 Apostrophes

- 3.6 Parentheses

- 3.7 Dashes

- 3.8 Hyphens

- 3.9 Punctuation: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 3 Punctuation

- 4.1 Commonly Confused Words

- 4.2 Spelling

- 4.3 Word Choice

- 4.4 Prefixes and Suffixes

- 4.5 Synonyms and Antonyms

- 4.6 Using Context Clues

- 4.7 Working with Words: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 4 Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?

- 5.1 Word Order

- 5.2 Negative Statements

- 5.3 Count and Noncount Nouns and Articles

- 5.4 Pronouns

- 5.5 Verb Tenses

- 5.6 Modal Auxiliaries

- 5.7 Prepositions

- 5.8 Slang and Idioms

- 5.9 Help for English Language Learners: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- 5.1 Word Order

- 5.2 Negative Statements

- 5.3 Count and Noncount Nouns and Articles

- 5.4 Pronouns

- 5.5 Verb Tenses

- 5.6 Modal Auxiliaries

- 5.7 Prepositions

- 5.8 Slang and Idioms

- 5.9 Help for English Language Learners: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 5 Help for English Language Learners

- 6.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

- 6.2 Effective Means for Writing a Paragraph

- 6.3 Writing Paragraphs: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 6 Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content

- 7.1 Sentence Variety

- 7.2 Coordination and Subordination

- 7.3 Parallelism

- 7.4 Refining Your Writing: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 7 Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?

- 8.1 Apply Prewriting Models

- 8.2 Outlining

- 8.3 Drafting

- 8.4 Revising and Editing

- 8.5 The Writing Process: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 8 The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?

- 9.1 Developing a Strong, Clear Thesis Statement

- 9.2 Writing Body Paragraphs

- 9.3 Organizing Your Writing

- 9.4 Writing Introductory and Concluding Paragraphs

- 9.5 Writing Essays: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 9 Writing Essays: From Start to Finish

- 10.1 Narration

- 10.2 Illustration

- 10.3 Description

- 10.4 Classification

- 10.5 Process Analysis

- 10.6 Definition

- 10.7 Comparison and Contrast

- 10.8 Cause and Effect

- 10.9 Persuasion

- 10.10 Rhetorical Modes: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 10 Rhetorical Modes

- 11.1 The Purpose of Research Writing

- 11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

- 11.3 Managing Your Research Project

- 11.4 Strategies for Gathering Reliable Information

- 11.5 Critical Thinking and Research Applications

- 11.6 Writing from Research: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 11 Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?

- 12.1 Creating a Rough Draft for a Research Paper

- 12.2 Developing a Final Draft of a Research Paper

- 12.3 Writing a Research Paper: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 12 Writing a Research Paper

- 13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

- 13.2 Citing and Referencing Techniques

- 13.3 Creating a References Section

- 13.4 Using Modern Language Association (MLA) Style

- 13.5 APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 13 APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting

- 14.1 Organizing a Visual Presentation

- 14.2 Incorporating Effective Visuals into a Presentation

- 14.3 Giving a Presentation

- 14.4 Creating Presentations: End-of-Chapter Exercises

- Chapter 14 Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas

- 15.1 Introduction to Sample Essays

- 15.2 Narrative Essay

- 15.3 Illustration Essay

- 15.4 Descriptive Essay

- 15.5 Classification Essay

- 15.6 Process Analysis Essay

- 15.7 Definition Essay

- 15.8 Compare-and-Contrast Essay

- 15.9 Cause-and-Effect Essay

- 15.10 Persuasive Essay

- Chapter 15 Readings: Examples of Essays

- United States History, Volume 2

- Social Psychology Principles

- Culture and Media

- Business Accounting

- Accounting for Managers

- Advanced Algebra

- business-accounting

- accounting-for-managers

- accounting-in-the-finance-world

- beginning-chemistry

- beginning-economic-analysis

- beginning-statistics

- theory-and-applications-of-economics

- theory-and-applications-of-macroeconomics

- theory-and-applications-of-microeconomics

- economics-principles-v1.0

- 11 economics-principles-v1.1

- 11 macroeconomics-principles-v2.0

- 11 microeconomics-principles-v1.0

- 11 microeconomics-principles-v2.0

- 11 policy-and-theory-of-international-economics

- 13 finance-banking-and-money-v1.0

- 13 finance-banking-and-money-v1.1

- 13 finance-banking-and-money-v2.0

- 13 finance-for-managers

- 13 policy-and-theory-of-international-finance

- 21st-century-american-government-and-politics

- advertising-campaigns-start-to-finish

- a-guide-to-perspective-analysis

- an-introduction-to-british-literature

- an-introduction-to-business-v1.0

- an-introduction-to-business-v2.0

- an-introduction-to-sustainable-business

- a-primer-on-communication-studies

- a-primer-on-politics

- beginning-management-of-human-resources

- beginning-organizational-change

- beginning-project-management-v1.0

- beginning-project-management-v1.1

- british-literature-through-history

- business-and-the-legal-and-ethical-environment

- business-and-the-legal-environment

- business-ethics

- business-strategy

- challenges-and-opportunities-in-international-business

- Com-1 an-introduction-to-group-communication

- communication-for-business-success

- communication-for-business-success-canadian-edition

- competitive-strategies-for-growth

- creating-services-and-products

- cultural-intelligence-for-leaders

- designing-business-information-systems-apps-websites-and-more

- enterprise-and-individual-risk-management

- entrepreneurship-and-sustainability

- geographic-information-system-basics

- getting-the-most-out-of-information-systems-a-managers-guide-v1.0

- getting-the-most-out-of-information-systems-a-managers-guide-v1.1

- getting-the-most-out-of-information-systems-v1.2

- getting-the-most-out-of-information-systems-v1.3

- getting-the-most-out-of-information-systems-v1.4

- getting-the-most-out-of-information-systems-v2.0

- global-strategy

- governing-corporations

- introduction-to-chemistry-general-organic-and-biological

- introduction-to-criminal-law

- job-searching-in-six-steps

- legal-aspects-of-commercial-transactions

- legal-aspects-of-property-estate-planning-and-insurance

- legal-basics-for-entrepreneurs

- management-principles-v1.0

- management-principles-v1.1

- managerial-economics-principles

- marketing-principles-v1.0

- marketing-principles-v2.0

- mass-communication-media-and-culture

- modern-management-of-small-businesses

- music-theory

- Nut-1an-introduction-to-nutrition

- OB-1an-introduction-to-organizational-behavior-v1.0

- OC-1an-introduction-to-organizational-communication

- online-marketing-essentials

- policy-and-theory-of-international-trade

- powerful-selling

- principles-of-general-chemistry-v1.0

- principles-of-general-chemistry-v1.0m

- psychology-research-methods-core-skills-and-concepts

- public-relations

- public-speaking-practice-and-ethics

- regional-geography-of-the-world-globalization-people-and-places

- sociological-inquiry-principles-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods

- sociology-brief-edition-v1.0

- sociology-brief-edition-v1.1

- sociology-comprehensive-edition

- strategic-management-evaluation-and-execution

- sustainable-business-cases

- the-law-corporate-finance-and-management

- the-law-sales-and-marketing

- the-legal-environment-and-advanced-business-law

- the-legal-environment-and-business-law-executive-mba-edition

- the-legal-environment-and-business-law-master-of-accountancy-edition

- the-legal-environment-and-business-law-v1.0

- the-legal-environment-and-business-law-v1.0-a

- the-legal-environment-and-foundations-of-business-law

- the-legal-environment-and-government-regulation-of-business

- JOBS

HISTORY OF LAW

Legal history or the history of law is the study of how law has evolved and why it changed. Legal history is closely connected to the development of civilisations and is set in the wider context of social history. Among certain jurists and historians of legal process it has been seen as the recording of the evolution of laws and the technical explanation of how these laws have evolved with the view of better understanding the origins of various legal concepts, some consider it a branch of intellectual history. Twentieth century historians have viewed legal history in a more contextualised manner more in line with the thinking of social historians. They have looked at legal institutions as complex systems of rules, players and symbols and have seen these elements interact with society to change, adapt, resist or promote certain aspects of civil society. Such legal historians have tended to analyse case histories from the parameters of social science inquiry, using statistical methods, analysing class distinctions among litigants, petitioners and other players in various legal processes. By analysing case outcomes, transaction costs, number of settled cases they have begun an analysis of legal institutions, practices, procedures and briefs that give us a more complex picture of law and society than the study of jurisprudence, case law and civil codes can achieve.

Contents

[hide] 1 Ancient world

2 Southern Asia

3 Eastern Asia

4 Islamic law

5 European laws 5.1 Roman Empire

5.2 Middle Ages

5.3 Modern European law

6 United States

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Ancient world[edit]

Main articles: Ma'at, Babylonian law, Ancient Greek law and Leviticus

See also: Urukagina, Hittite laws and Ostracism

Ancient Egyptian law, dating as far back as 3000 BC, had a civil code that was probably broken into twelve books. It was based on the concept of Ma'at, characterised by tradition, rhetorical speech, social equality and impartiality.[1] By the 22nd century BC, Ur-

Southern Asia[edit]

Main articles: Manu Smriti, Yajnavalkya Smriti, Arthashastra and Dharmasastra

See also: Classical Hindu law, Classical Hindu law in practice and Hindu law

The Constitution of India is the longest written constitution for a country, containing 444 articles, 12 schedules, numerous amendments and 117,369 words

Ancient India and China represent distinct traditions of law, and had historically independent schools of legal theory and practice. The Arthashastra, dating from the 400 BC, and the Manusmriti from 100 AD were influential treatises in India, texts that were considered authoritative legal guidance.[5] Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and pluralism, and was cited across South East Asia.[6] But this Hindu tradition, along with Islamic law, was supplanted by the common law when India became part of the British Empire.[7] Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and Hong Kong also adopted the common law.

Eastern Asia[edit]

Main articles: Traditional Chinese law, Tang Code and Great Qing Legal Code

The eastern Asia legal tradition reflects a unique blend of secular and religious influences.[8] Japan was the first country to begin modernising its legal system along western lines, by importing bits of the French, but mostly the German Civil Code.[9] This partly reflected Germany's status as a rising power in the late nineteenth century. Similarly, traditional Chinese law gave way to westernisation towards the final years of the Qing dynasty in the form of six private law codes based mainly on the Japanese model of German law.[10] Today Taiwanese law retains the closest affinity to the codifications from that period, because of the split between Chiang Kai-

Yassa of the Mongol Empire

Islamic law[edit]

Main article: Sharia

See also: Fiqh, Islamic ethics and Early reforms under Islam

One of the major legal systems developed during the Middle Ages was Islamic law and jurisprudence. A number of important legal institutions were developed by Islamic jurists during the classical period of Islamic law and jurisprudence, One such institution was the Hawala, an early informal value transfer system, which is mentioned in texts of Islamic jurisprudence as early as the 8th century. Hawala itself later influenced the development of the Aval in French civil law and the Avallo in Italian law.[14]

European laws[edit]

Roman Empire[edit]

Main article: Roman law

Roman law was heavily influenced by Greek teachings.[15] It forms the bridge to the modern legal world, over the centuries between the rise and decline of the Roman Empire.[16] Roman law, in the days of the Roman republic and Empire, was heavily procedural and there was no professional legal class.[17] Instead a lay person, iudex, was chosen to adjudicate. Precedents were not reported, so any case law that developed was disguised and almost unrecognised.[18] Each case was to be decided afresh from the laws of the state, which mirrors the (theoretical) unimportance of judges' decisions for future cases in civil law systems today. During the 6th century AD in the Eastern Roman Empire, the Emperor Justinian codified and consolidated the laws that had existed in Rome so that what remained was one twentieth of the mass of legal texts from before.[19] This became known as the Corpus Juris Civilis. As one legal historian wrote, "Justinian consciously looked back to the golden age of Roman law and aimed to restore it to the peak it had reached three centuries before."[20]

Middle Ages[edit]

King John of England signs the Magna Carta

Main articles: Early Germanic law, Anglo-

See also: Germanic tribal laws, Visigothic Code, Early Irish law, Dōm, Blutgericht, Magna Carta and Schwabenspiegel

During the Byzantine Empire the Justinian Code was expanded and remained in force until the Empire fell, though it was never officially introduced to the West. Instead, following the fall of the Western Empire and in former Roman countries, the ruling classes relied on the Theodosian Code to govern natives and Germanic customary law for the Germanic incomers -

Modern European law[edit]

Main articles: Napoleonic code, Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch and English law

The two main traditions of modern European law are the codified legal systems of most of continental Europe, and the English tradition based on case law.

As nationalism grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, lex mercatoria was incorporated into countries' local law under new civil codes. Of these, the French Napoleonic Code and the German Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch became the most influential. As opposed to English common law, which consists of massive tomes of case law, codes in small books are easy to export and for judges to apply. However, today there are signs that civil and common law are converging. European Union law is codified in treaties, but develops through the precedent set down by the European Court of Justice.

United States[edit]

The United States legal system developed primarily out of the English common law system (with the exception of the state of Louisiana, which continued to follow the French civilian system after being admitted to statehood). Some concepts from Spanish law, such as the prior appropriation doctrine and community property, still persist in some US states, particularly those that were part of the Mexican Cession in 1848.

Under the doctrine of federalism, each state has its own separate court system, and the ability to legislate within areas not reserved to the federal government.

History of Lawyers

History of Lawyers

The first people who could be called lawyers were the great speakers of ancient Greece. Individual people were presumed to present a defense their own cases, but that was circumvented by having a friend better at speaking do it for you. Around the middle of the fourth century, the Greeks got rid of the request for a friend. Second, a more serious obstacle, which the Greek orators never completely overcame, was the rule that no one could take a fee to plead the case of another. This law was disregarded in practice, but was never abolished, which meant that orators could never present themselves as legal professionals or experts. They had to uphold the ruse that they were an ordinary citizen helping out a friend for free, and so they could never organize into a real profession,with professional associations and titles, like their modern lawyers. If one narrows the definition to those men who could practice the legal profession openly and legally, then the first lawyers would have to be the orators of ancient Rome A law enacted in 204 BC barred Roman advocates from taking fees, but the law was widely ignored.The ban on fees was abolished by Emperor Claudius who legalized advocacy as a profession and allowed the Roman advocates to become the first lawyers who could practice openly—but he also imposed a fee ceiling of 10,000 sesterces. This was apparently not much money; the Satires of Juvenal complain that there was no money in working as an advocate.Like their Greek contemporaries, early Roman advocates were trained in rhetoric not law, and the judges before whom they argued were also not law-

A Brief History of Attorneys

Formal systems of laws have existed since Hammurabi erected his code in the courtyards of temples during his reign as ruler of the Babylonian empire early in the 18th century B.C.E., and since then there has been a need for individuals to study and interpret those laws. However the history of attorneys, those who are professionals dedicated exclusively to the study, interpretation and application of the law is much more recent.

The sophists of ancient Athens were probably the first who existed as a class of people who were considered as something akin to lawyers. However, there were some societal situations that inhibited the development of a legal profession. One was an Athenian law requiring citizens to plead their own cases. This eroded over time as more and more requested friends to act as an advocate for them. More importantly, though, was the law the disallowed anyone from exacting a fee to plead for someone else, thereby preventing anyone from presenting themselves as a legal expert.

The first real development in the history of attorneys occurs in the ancient Roman Empire. During the reign of the Emperor Claudius in the first century C.E., the ban on fees is abolished and legal advocates are allowed professional status. During this time, a class of legal professionals quickly evolves and by the late fourth century a true legal profession has taken shape, dedicated to the study and practice of law, with regulations and standards in place for guidance.

During the Middle Ages, paralleling the collapse of the Roman Empire in the west, the legal profession essentially disappears. Within the Church, a body of men pursued the study of Canon Law, but practice in civil law was rare, if it existed at all. By the mid-

By the end of the American and French revolutions, a greater need for a legal profession manifests itself as the power of monarchies is being broken. With this wearing away of absolute power in the hands of a single individual, and varieties of democratic states appearing, the legal profession grows. With the concept of all citizens equal before the law being a cornerstone of democratic philosophy, a greater need for attorneys is evinced. A brief history of attorneys reveals a movement from a loose concept an advocate who offers assistance to an individual appearing before the council of the Greek city-

History of law

History of lawThe history of law is the history of our race, and the embodiment of its experience. It is the most unerring monument of its wisdom and of its frequent want of wisdom. The best thought of a people is to be found in its legislation; its daily life is best mirrored in its usages and customs, which constitute the law of its ordinary transactions.

There never has existed, and it is entirely safe to say that there never will exist, on this planet any organization of human society, any tribe or nation however rude, any aggregation of men however savage, that has not been more or less controlled by some recognized form of law. Whether we accept the fashionable, but in this regard wholly unsupported and irrational theory of evolution that would develop civilization from barbarism, barbarism from savagery, and the existence of savage men from a simian ancestry, or whether we adopt the more reasonable theory, sustained by the uniform tenor of all history, that barbarism and savagery are merely lapses from a primordial civilization, we find man at all times and under all circumstances, so far as we are informed by the records which he has left, living in society and regulating his conduct and transacting his affairs in subordination to some rules of law, more or less fixed, and recognized by him to be binding upon him, even though he has oftentimes been in rebellion against some of their provisions.

The recognition of the existence of law outside of himself, and yet binding upon him, is inherent in man's nature, and is a necessity of his being. And this is as much as to say that the very existence of human society is dependent upon law imposed by some superior power. While from our present standpoint the ultimate finite existence is that of the individual, and all true philosophy recognizes that society exists for the individual, and not the individual for society, yet it is also true that the individual is intended to exist in society, and that he must in many things subordinate his own will to that of society, and inasmuch as society can not exist without law, it is a necessary deduction of reason that the existence of law is coeval with that of the human race.

For, if the origin of law were to be sought in compact, a similar compact would suffice to abrogate it; and if it depended on the force of the majority, the wrongfulness of disobedience to its behests would depend entirely upon its discovery and manifestation to the world.

Suppose two shipwrecked men thrown upon a desert island, far removed from all human society, far removed from all its agencies and instrumentalities for the prevention and punishment of crime, and one in wantonness kills the other, is the act any less a crime, because it may never be discovered, because it may never be reached by the avenging arm of justice, because the social compact has never been in force in that remote region of the earth. Our conscience and our common sense rebel against the inference of any distinction between such a crime and that of the ordinary murderer within the pale of civilization.